FORCE-ing The Issue: Artivism Upsetting Rape Culture

The culture-jamming duo scored some major media nods for their Playboy parody website, which revised Playboy’s guide to parties and campus life thusly: “A good college party is all about everyone having a good time. Consent is all about everyone having a good time. Rape is only a good time if you’re a rapist. And fuck those people.” Got that?

FORCE also made a splash with Pink Loves Consent, in which they posed as Victoria’s Secret and offered consent-themed, anti-rape panties — handily fooling and educating many in the process. (And disappointing those who wanted to actually buy these protest panties.) The “Operation Panty Drop” antic did include leaving these feminist underthings in several Victoria’s Secret stores in North America and Europe. Why, consent looks so pretty on you!

To mark Sexual Assault Awareness Month, One+Love wanted to shine even more light on FORCE — especially since they’re currently busy stitching together The Monument Quilt, a project meant to gather survivors while unraveling the culture of rape. Here is an excerpt of the phone interview I conducted with Nagle….

On what inspired The Monument Quilt:

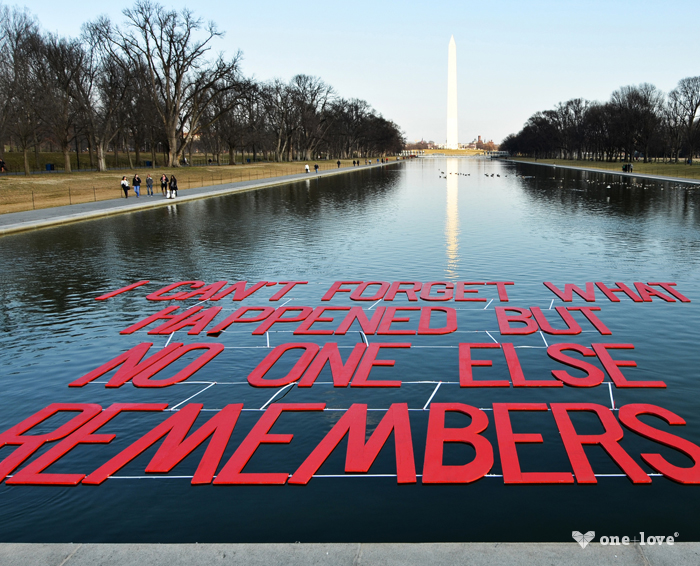

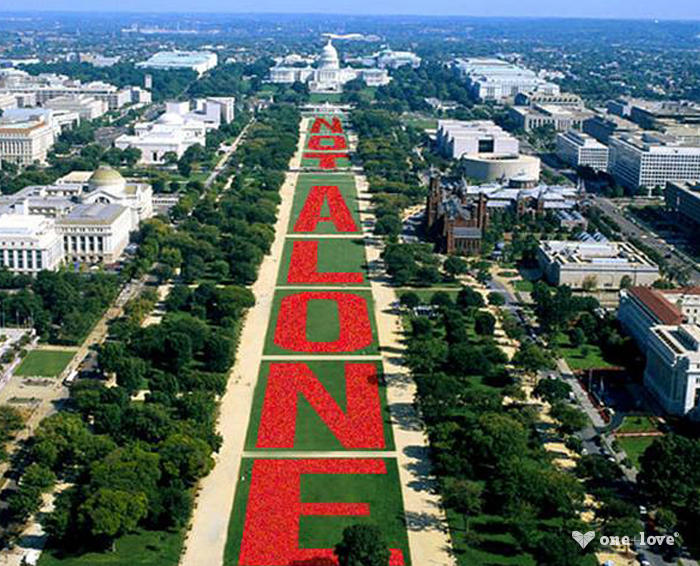

“We got this idea of monuments from this writer-psychologist Judith Herman. She wrote a book called Trauma and Recovery. And in it she’s talking about the similarities between survivors and veterans of war and survivors of rape and abuse. For veterans of war, we have these monuments that serve as a connection so people who’ve had this violent experience outside of the social norm and the social compact can return to communities, feel welcome, and have a space to connect with people and that’s part of the healing process for PTSD. And for rape survivors, the healing process is confined to the private realm. And there are no public spaces for rape survivors to heal, and there are no public monuments to rape.

And so that got us thinking about there being a permanent monument, which is the end-goal and the quilt is kind of a call and demonstration for a permanent monument. So it’s a community art project that lots of people across the country are engaging in. And through people’s participation, we’re creating space for survivors to heal and introducing people and our culture to the idea that it can exist and it should exist.”

On how queerness informs FORCE:

“So, I’m queer — so I think that the work has that lens through me directing it and that being my identity. And in my personal experience what I’ve found from queer community is a lot of language and a lot of tools to talk about sexuality and sex, and so I think when it comes to the work that we do to promote consent, a lot of the sex-positive queer spaces that I’ve been part of really influenced the language that we use.”

On the concept of “safe space”:

“A lot of the models that we have in our culture for survivors to publically share their story — the role of the survivor sharing the story is for the survivor to educate the public. The roles are reversed in The Monument Quilt. Survivors are still publically sharing their story, but the role of the public to support the survivor. It’s a subtle difference, but I think it’s also profound. So it’s a space where the needs of survivors are placed first, and in that space the public is being educated and there’s this awareness element, but the priority of the space is healing.

The couple displays we’ve done of The Monument Quilt and even when we gathered people together in workshops, the emphasis on healing and on the survivors’ experience to me feels really different as a survivor. And it’s not something that just happens. We do a LOT of work to try and create that space. When we do the quilt display, there’s a border that goes around the edges of the quilt that has basically a trigger warning and also has some grounding techniques to remind people to breathe. And when we’ve done public displays, people will walk up, and I’ll see people read the border, and see what it’s about, and then walk away. And I feel really good about that moment. Because what we’re doing is we’re giving people a choice about how they wanna enter the space and if they wanna enter the space.

So when I think when it comes to creating safer spaces for survivors, it’s all about choices. Because the experience of sexual violence is having someone take a choice away from you. So in the project and in the space we’re creating for survivors, everything is optional. And everything is what the individual survivor wants for their own personal process.

We have counselors at the space. We have a resources guide, postcards with self-care tips. So even the space we’re creating is about a choice. Does every survivor need to publically share their story in order to heal? No, for some people that might not be part of their healing process. But if we look at the culture in the United States right now, people don’t have that option. If you’re going to publically disclose that you’ve survived rape, you risk judgment, pity, ignorance, and retaliation. So if you look at the consequences that survivors often go through, it’s not really an option. So by creating public spaces, we’re giving people access to another choice and access to another place to heal that I think survivors need and deserve.”

Contribute to The Monument Quilt Tour!

Recent Comments